By Jeanne Tarrant, Endangered Wildlife Trust – South Africa

“Dad! There’s a frog in the kitchen!” – this was something I regularly shouted out growing up in the countryside town of Underberg in the southern Drakensberg Mountains of South Africa. The call was of course for my father to remove said creature from my midst! I was not afraid of them necessarily, but they did gross me out a bit – and I certainly didn’t have much interest in them…yet! Little did I know that these creatures would form the focus of my adult career – and that their protection would become a life-long passion. The offending animal in the case of my childhood encounters I now know is the Guttural Toad, Sclerophrys gutturalis, so called because of it’s deep guttural call. Now unafraid to pick them up, I know that these toads have the most beautiful golden eyes, and a fascinating breeding behavior governed by female mate-selection. I now also know that the diversity of frogs extends well beyond just that of the toads, and that each of the 8000-odd species has a fascinating life-history and incredible adaptations that allow them to survive in a huge range of habitats, including sometimes very extreme conditions. Such as the Maluti River Frog, Amietia vertebralis, from Lesotho – which became my first study species – and is adapted to high-altitude rivers that freeze over in winter, when these frogs can be seen swimming under the ice. The species also has an umbrella-like outgrowth above their pupil inside their eyes – an adaptation to the extreme high UV at these high altitudes.

So, how did I make the journey from screeching for toad removal, to studying one of the region’s largest river frog species, to ultimately a career spanning 15 years with a primary focus on frogs? Having lived abroad in the UK for several years after my undergraduate studies, I was ready to return to South Africa, and having a Zoology degree under my belt (but completely unused so far), I was keen to enter the field of conservation and to start exploring my own country. On the flight back to South Africa, I sat next to a woman who told me about a correspondence degree in Environmental Science through the North-West University (NWU). With some trepidation, I enrolled for an Honors degree, and set off to Potchefstroom to register and gather course material. It turned out that a requirement for the degree was a practical dissertation. I had no idea what to do it on – I thought something like butterflies might be nice – until mentioning the frogs I shouted about in my childhood home. Well, that was that. I was immediately introduced to Professor Louis du Preez, who asked me “Do you like frogs?”. I think my face may have looked like a box of frogs, but so the journey began. There was a taxonomic puzzle to be solved on river frogs in Lesotho and the Drakensberg – not far from where I grew up. My first field trip to the Central Berg had me convinced that this beat a day in the office in London. By far.

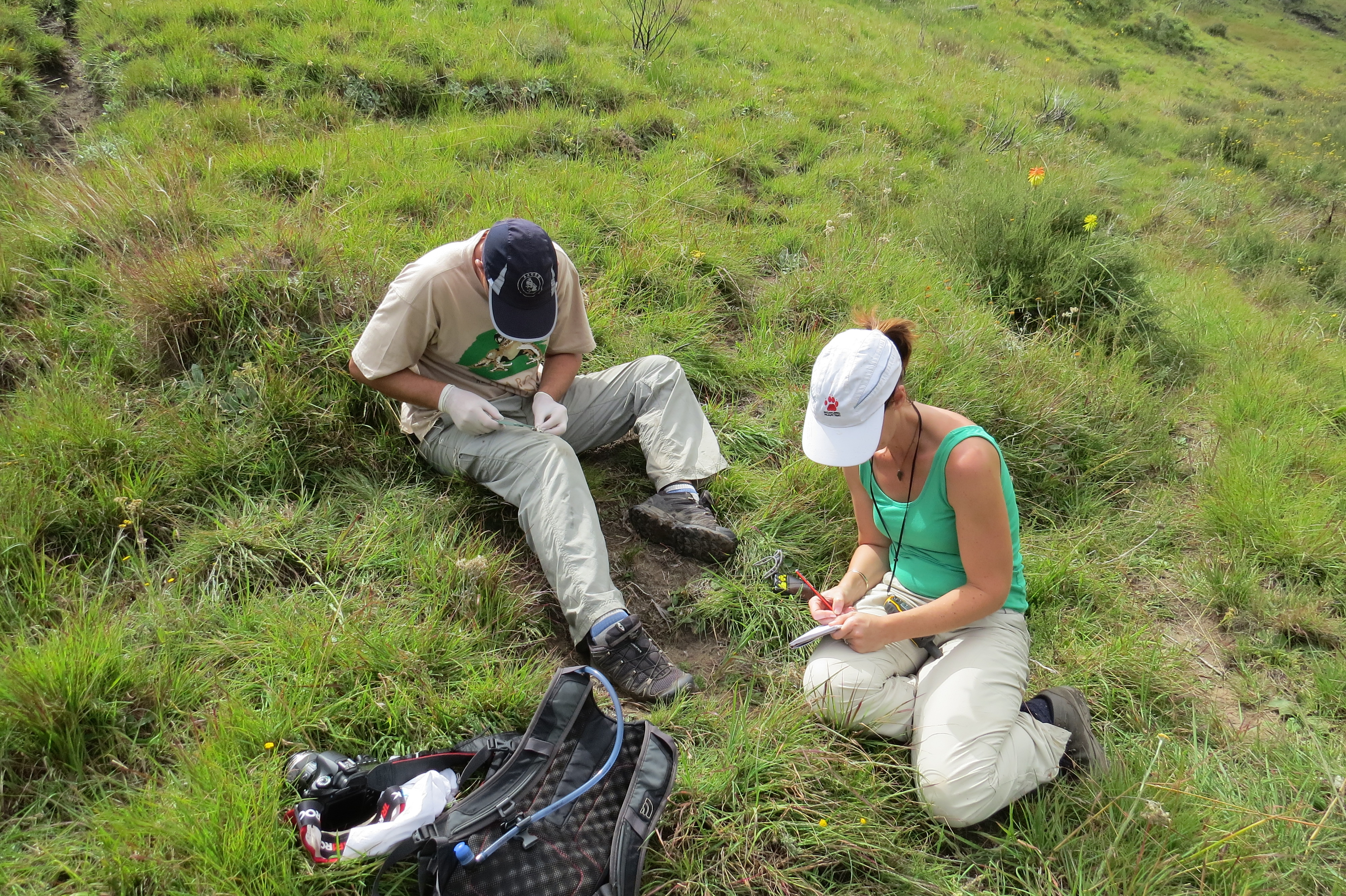

The mountain-based frog study was upgraded to a MSc and followed by a PhD looking at South Africa’s threatened frog species, in particular in relation to the amphibian fungal disease, chytrid. I also focused on the Pickersgill’s Reed Frog, Hyperolius pickersgilli – surveying over 80 sites along the coast of KwaZulu-Natal – where the species was known only from 8 localities and was Critically Endangered. Since then, the species has become the focus of a comprehensive and collaborative action plan, is now known from over 40 sites, and has been down-listed to Endangered. I was then fortunate enough to continue this work through both a post-doc through NWU at the same time as joining the Endangered Wildlife Trust, one of South Africa’s largest conservation NGOs. Very little NGO-based frog conservation work had taken place up until this point (around 2012), but the timing was really good as in 2011 a conservation strategy had been published for the region’s frog species. This provided a comprehensive guide to where and what conservation effort was needed, and building off my research, I established the Threatened Amphibian Programme.

As an NGO-based organization, our work is entirely donor-dependent. And so, I entered the world of fund-raising! This was challenging, as was keeping track of budgets! With support from colleagues from the EWT, we managed to secure an initial first small grant for work in the Amathole mountains for the Critically Endangered Amathole Toad, Vandijkophrynus amatolicus. For three years, I was the sole face of the programme, until 2015 when a national government grant was secured to implement alien plant clearing work at sites for Pickergsill’s Reed Frog. This was a game-changer in that it really helped developed the social component of the programme. The programme now employs nine people, and our work covers three provinces, nine focal species, and a snake! Our social change and educational work are pivotal to the success of the programme.

Without the fantastic team that now makes up the Threatened Amphibian Programme, my work could not cover the scope that it does. The recent inclusion of several Western Cape species has not only allowed me to travel to exciting new areas, but also be able to work with brilliant researchers and conservationists. Conservation is a challenging career – not just because it relies on hard work and is entirely funding-dependent (especially not easy when frogs attract relatively little funding), but because it can leave one feeling very despondent at the state of the world and the feeling that one is fighting a losing battle. But it is also an incredibly rewarding career. I am so privileged to visit beautiful places in the quest to protect them, and understand more about the species that inhibit them, to working with an amazing group of super passionate people, and of course to have learnt – and to keep learning something new every day – about these beautiful, fun, and fascinating animals – the frogs! In themselves, they are wonderful, but they also serve to connect us to the natural world and inspire learning about just about everything else – from the insects they rely on for food, to freshwater ecology, to bird calls when needing to identify them from their vast range of sounds.

I feel truly privileged to have been able to enter this fascinating world, and hope to inspire similar journeys, especially for those who might be sitting at home with a fear or phobia of frogs…or snakes! For people entering the realm of amphibian conservation and research, it may seem daunting that lofty qualifications are a necessity, or that jobs are scarce. From what I have learnt over the last 15 years – in a career that has been somewhat unexpected! –is that a passion for knowledge, a willingness to learn from those you met along the way, and an openness to taking every opportunity as well as determined hard work, can lead to a very rewarding and satisfyingly unique career. Some words of advice would be to get out of your comfort zone, stretch yourself and know you can do more than you ever thought you could.

In my case, the Threatened Amphibian Programme with the Endangered Wildlife Trust was a continuation of my post-graduate work, but also a vision of the first NGO-based programme carrying out direct conservation action for frogs. I have been fortunate to have had the support in nurturing this vision into what the programme is today. Another aspect that really helps is that amphibian researchers are genuinely a great bunch of people! In my experience, they are amongst the few biologists where a diverse mix of extraordinary personalities work together towards the common goal of ensuring that their favourite four-legged creatures are understood, appreciated and protected. I’ve met and worked with some of the most fabulous, like-minded, knowledgeable people and look forward to continuing these relationships for a long time to come.

Sharing how important the focus of our work is, is also a critical element of conservation work. Our study creatures are often misunderstood, undervalued, under-funded and even persecuted. Communicating that the opposite is in fact true is vital to garnering an appreciation of these animals and can also be a lot of fun! For example, our Leap Day for Frogs campaign held annually invites people from across South Africa to get excited about frogs! Some of my most rewarding moments have been chatting to kids on frogging evenings and watching the enlightenment on their faces as they learn something for the first time. While it can be easy to sink into the doom and gloom of extinction messages, it is vital also to keep a sense of hope, to inspire our next generation to pick up the baton. In the words of Noam Chomsky “Optimism is a strategy for making a better future. Because unless you believe that the future can be better, you are unlikely to step up and take responsibility for making it so”.

Biography

Dr Jeanne Tarrant

Bachelor in Zoology (2001) Rhodes University, South Africa, Masters in Environmental Science (2008) and PhD in Zoology at North-West Univeristy, Potchefstroom, South Africa.

Jeanne manages the Endangered Wildlife Trust’s Threatened Amphibian Programme (TAP in South Africa). This is the only NGO with a focus on frog conservation, using threatened species as flagships to:

- protect the critical freshwater and terrestrial habitats

- improve the management of important amphibian habitat

- use research to monitor species and habitats to support conservation action

- promote behavioural change that reflects increased knowledge and recognition of the importance of frogs and their habitats.

Jeanne is responsible for project design and coordination, specialist knowledge, partner and donor relations, fundraising and project management. Almost all of her work is linked to threatened frog species, which are usually associated with very limited distribution ranges and specific habitat types, most of which are not protected or well-managed. In 2020, Jeanne was recipient of the Whitley Award, or “Green Oscar” for her work in conservation.

Fun facts: I took up mountain biking at age 40, I try to find time for yoga regularly, I increasingly love gardening and getting grubby! I have two boys, who get very upset if I don’t catch the snakes spotted in the garden for them if they are not around!

Favourite amphibian: Kloof Frog, Natalobatrachus bonebergi – they are handsome little frogs that have a unique egg-laying technique – attaching them to branches or rocks above water, females then watch over them.

Twitter handle: JeanneT4Frogs, #FrogLady

Languages: English, some Afrikaans and isiZulu

I like to start a Amphibian program in the village of Velingara Africa to help the people with mosquitoes problem.

I like to start the same NGO for Ethiopia, what do I need to do? I need your advice.